Bridging the gap between IaC and Schema Management

Introduction

When we started building Atlas a couple of years ago, we noticed that there was a substantial gap between what was then considered state-of-the-art in managing database schemas and the recent strides from Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC) to managing cloud infrastructure.

In this post, we review that gap and show how Atlas – along with its Terraform provider – can bridge the two domains.

As an aside, I usually try to keep blog posts practical and to the point, but occasionally think it’s worth it to zoom out and explain the grander ideas behind what we do.

If you’re looking for a quick and practical explanation of working with Atlas and Terraform, I recommend this YouTube video.

Why Infrastructure-as-Code

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) refers to the practice of managing and provisioning infrastructure through machine-readable configuration files, instead of utilizing traditional interactive configuration tools. This approach makes for automated, consistent, and repeatable deployment of environments that are faster and less error-prone than previous, more manual approaches.

Terraform, a popular open-source tool created by HashiCorp, is the most prominent implementation of the IaC concept. With Terraform, organizations can describe the desired state of their infrastructure in a simple configuration language (HCL) and let Terraform plan and apply these changes in an automated way.

Terraform (and IaC in general) has taken the software engineering world by storm in recent years. As someone who had the dubious pleasure of managing complex cloud infrastructure manually, using what is today jokingly called "ClickOps", I can mention a few properties of IaC that I believe contributed to this success:

-

Declarative – Terraform is built on a declarative workflow, which means that users only define the final (desired) state of their system. Terraform is responsible for inspecting the target environment, calculating the difference between the current and desired states, and building a plan for reconciling between those two states.

Cloud infrastructures are becoming increasingly complex, comprising thousands of different, interconnected components. Declarative workflows greatly reduce the mental overhead of planning changes to such environments.

-

Automated – Many engineers can attest that manually provisioning a new environment used to take days, even weeks! Once Terraform generates a plan for changing environments, the process runs automatically and finishes in a matter of minutes.

-

Holistic – With Terraform, it is possible to capture all of the resources and configurations required to provision an application as one interconnected and formally defined dependency graph. Deployments become truly reproducible and automated, with no dangling or manually provisioned dependencies.

-

Self-healing – Finally, these three properties converge to support a self-healing tool that can detect and fix drift on its own. Whenever drift occurs, it is only a matter of re-running Terraform to shift from the current state back to the desired one.

Comparing IaC with Schema Management Tools

Next, let’s discuss the current state of database schema management tools (often called schema migration tools) by contrasting them with the properties of IaC.

-

Imperative – If Terraform embodies the declarative approach, then schema management tools often exemplify the opposite, imperative (or revision-based) approach. In this case, we don’t provide the tools with the what (the desired state of the database), but the how (what SQL commands need to run to migrate the database from the previous version to the next).

-

Semi-automated – Migration tools were revolutionary when they came out a decade ago. One idea stood as one of the harbingers of the GitOps philosophy: that database changes should not be applied manually but first checked into source control and then applied automatically by a tool.

Today’s migration tools automate two aspects of schema management: 1) execution and 2) tracking which migrations were already executed on a target database.

Compared to modern IaC tools, however, they are fairly manual. In other words, they leave the responsibility of planning and verifying the safety of changes to the user.

-

Fragmented – As we described above, one of the most pleasant aspects of adopting the IaC mindset is having a unified, holistic description of your infrastructure, to the point where you can entirely provision it from a single terraform apply command.

For database schema management, common practices are anything but holistic. In some cases, provisioning the schema might happen 1) when application servers boot, before starting the application, or 2) while it runs as an init container on Kubernetes.

In fact, some places (yes, even established companies) still have developers manually connect (with root credentials) to the production database to execute schema changes!

-

A pain to fix – When a migration deployment fails, many schema management tools will actually get in your way. Instead of worrying about fixing the issue at hand, you now need to worry about both your database and the way your migration tool sees it (which have now diverged).

Bridging the Gap

After describing the gap between IaC and database schema management in more detail, let’s delve into what it would take to bridge it. Our goal is to have schema management become an integral part of your day-to-day IaC pipeline so that you can enjoy all the positive properties we described above.

To integrate schema change management and IaC, we would need to solve two things:

- A diffing engine capable of supporting declarative migration workflows, such that an engine should be capable of:

- Loading the desired schema of the database in some form

- Inspecting the current schema of the database

- Calculating a safe migration plan automatically

- A Terraform Provider that wraps the engine as a Terraform resource, which can then seamlessly integrate into your overall application infrastructure configuration.

How Atlas drives Declarative Migrations

Atlas is a language-agnostic tool for managing and migrating database schemas using modern DevOps principles. It is different from Terraform in many ways, but similar enough to have received the informal nickname "Terraform for Databases".

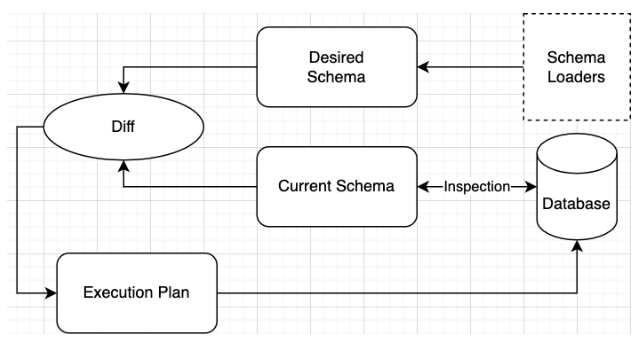

At its core lie three capabilities that make it ideal to apply a declarative workflow to schema management:

- Schema loaders

- Schema inspection

- Diffing and planning

Let’s discuss each of these capabilities in more detail.

Schema loaders

Every declarative workflow begins with the desired state - what we want the system to look like. Using a mechanism called "schema loaders" Atlas users can provide the desired schema in many ways. For example:

Plain SQL

Atlas users can describe the desired schema of the database using plain SQL DDL statements such as:

CREATE TABLE users (

Id int primary key,

Name varchar(255)

)

Atlas HCL

Alternatively, users can use Atlas HCL, a configuration language that shares Terraform’s configuration language foundations:

table "users" {

schema = schema.public

column "id" {

type = int

}

column "name" {

type = varchar(255)

}

column "manager_id" {

type = int

}

primary_key {

columns = [

column.id

]

}

}

A live database

In addition, users can provide Atlas with a connection to an existing database which in turn Atlas can inspect and use as the desired state of the database.

External Schemas (ORM)

Finally, Atlas has an easily extensible design which makes writing plugins to load schemas from external sources a breeze. For example, Atlas can read the desired schema of the database directly from your ORM, using a simple integration.

Schema inspection

Once Atlas understands the desired state of the database, it needs to inspect the existing database to understand its current schema. This is done by connecting to the target database and querying the database’s information schema to construct a schema graph (an in-memory representation of all the components in the database and their connections).

Diffing and planning

The next phase involves calculating the difference ("diffing") between the desired and current states and calculating an execution plan to reconcile this difference. Because resources are often interconnected, Atlas must create a sensible order of execution using algorithms such as Topological Sort to ensure, for example, that dependencies on a resource are removed before it is dropped.

In addition, each database engine has its own peculiarities and limitations to take into account when creating an execution plan. For example, adding a default value to a column in an SQLite database must be performed in a multiple-step plan that looks similar to this:

-- Planned Changes:

-- Create "new_users" table

CREATE TABLE `new_users` (`id` int NOT NULL, `greeting` text NOT NULL DEFAULT 'shalom')

-- Copy rows from old table "users" to new temporary table "new_users"

INSERT INTO `new_users` (`id`, `greeting`) SELECT `id`, IFNULL(`greeting`, 'shalom') AS `greeting` FROM `users`

-- Drop "users" table after copying rows

DROP TABLE `users`

-- Rename temporary table "new_users" to "users"

ALTER TABLE `new_users` RENAME TO `users`

Atlas in action

What does this workflow look like in practice? As you can see in Atlas's "Getting Started" guide, suppose we made a

change to our desired schema that adds a new table named blog_posts (this change may be described in a plain SQL file,

an HCL file or even in your ORM's data model).

To apply the desired schema on a target database you would use the schema apply command:

atlas schema apply \

-u "mysql://root:pass@localhost:3306/example" \

--to file://schema.sql \

--dev-url "docker://mysql/8/example"

After which Atlas will generate a plan:

-- Planned Changes:

-- Create "blog_posts" table

CREATE TABLE `example`.`blog_posts` (`id` int NOT NULL, `title` varchar(100) NULL, `body` text NULL, `author_id` int NULL, PRIMARY KEY (`id`), INDEX `author_id` (`author_id`), CONSTRAINT `author_fk` FOREIGN KEY (`author_id`) REFERENCES `example`.`users` (`id`))

Use the arrow keys to navigate: ↓ ↑ → ←

? Are you sure?:

▸ Apply

Abort

Observing this example, you may begin to understand how Atlas earned its nickname the "Terraform for Databases."

Integrating with Terraform

The second piece of bridging the gap is to create a Terraform Provider that wraps Atlas and allows users to define resources that represent the schema definition as part of your infrastructure.

Ariga (the company behind Atlas) is an official HashiCorp Tech Partner that publishes the Atlas Terraform Provider, which was created to solve this problem precisely.

Using the Atlas Terraform Provider, users can finally provision their database instance and its schema in one holistic definition. For example, suppose we provision a MySQL database using AWS RDS:

// Our RDS-based MySQL 8 instance.

resource "aws_db_instance" "atlas-demo" {

identifier = "atlas-demo"

instance_class = "db.t3.micro"

engine = "mysql"

engine_version = "8.0.28"

// Some fields skipped for brevity

}

Next, we load the desired schema from an HCL file, using the Atlas Provider:

data "atlas_schema" "app" {

src = "file://${path.module}/schema.hcl"

}

Finally, we use the atlas_schemaresource to apply our schema to the database:

// Apply the normalized schema to the RDS-managed database.

resource "atlas_schema" "hello" {

hcl = data.atlas_schema.app.hcl

url = "mysql://${aws_db_instance.atlas-demo.username}:${urlencode(random_password.password.result)}@${aws_db_instance.atlas-demo.endpoint}/"

}

You can find a full example here.

When we run terraform apply, this is what will happen:

- Terraform will provision the RDS database using the AWS Provider

- Terraform will use Atlas to inspect the existing schema of the database and load the desired state from a local HCL file.

- Atlas will calculate for Terraform a SQL plan to reconcile between the two.

And this is how it may look like in the Terraform plan:

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# atlas_schema.hello will be created

+ resource "atlas_schema" "hello" {

+ hcl = <<-EOT

table "posts" {

schema = schema.app

column "id" {

null = false

type = int

}

column "user_id" {

null = false

type = int

}

column "title" {

null = false

type = varchar(255)

}

column "body" {

null = false

type = text

}

primary_key {

columns = [column.id]

}

foreign_key "posts_ibfk_1" {

columns = [column.user_id]

ref_columns = [table.users.column.id]

on_update = NO_ACTION

on_delete = CASCADE

}

index "user_id" {

columns = [column.user_id]

}

}

table "users" {

schema = schema.app

column "id" {

null = false

type = int

}

column "user_name" {

null = false

type = varchar(255)

}

column "email" {

null = false

type = varchar(255)

}

primary_key {

columns = [column.id]

}

}

schema "app" {

charset = "utf8mb4"

collate = "utf8mb4_0900_ai_ci"

}

EOT

+ id = (known after apply)

+ url = (sensitive value)

}

# aws_db_instance.atlas-demo will be created

+ resource "aws_db_instance" "atlas-demo" {

// .. redacted for brevity

+ }

And that's how you bridge the gap between IaC and schema management!

Conclusion

In this blog post, we reviewed some exceptional properties of Infrastructure-as-Code tools, such as Terraform, that have led to their widespread adoption and success in the industry. We then reviewed the current state of a similar problem, database schema management, in contrast to these properties. Finally, we showcased Atlas’s ability to adapt some IaC principles into the domain of schema management and how we can unify the two domains using the Atlas Terraform Provider.

How can we make Atlas better?

We would love to hear from you on our Discord server ❤️.